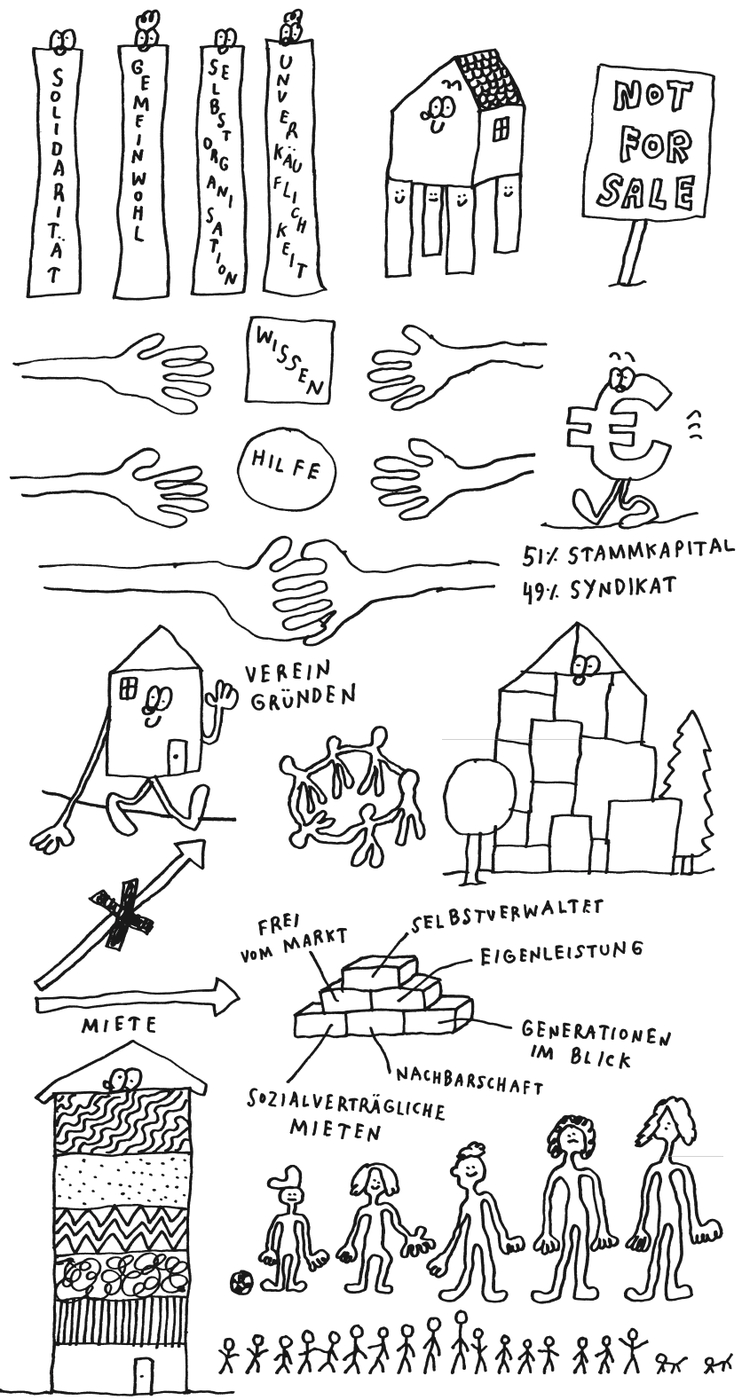

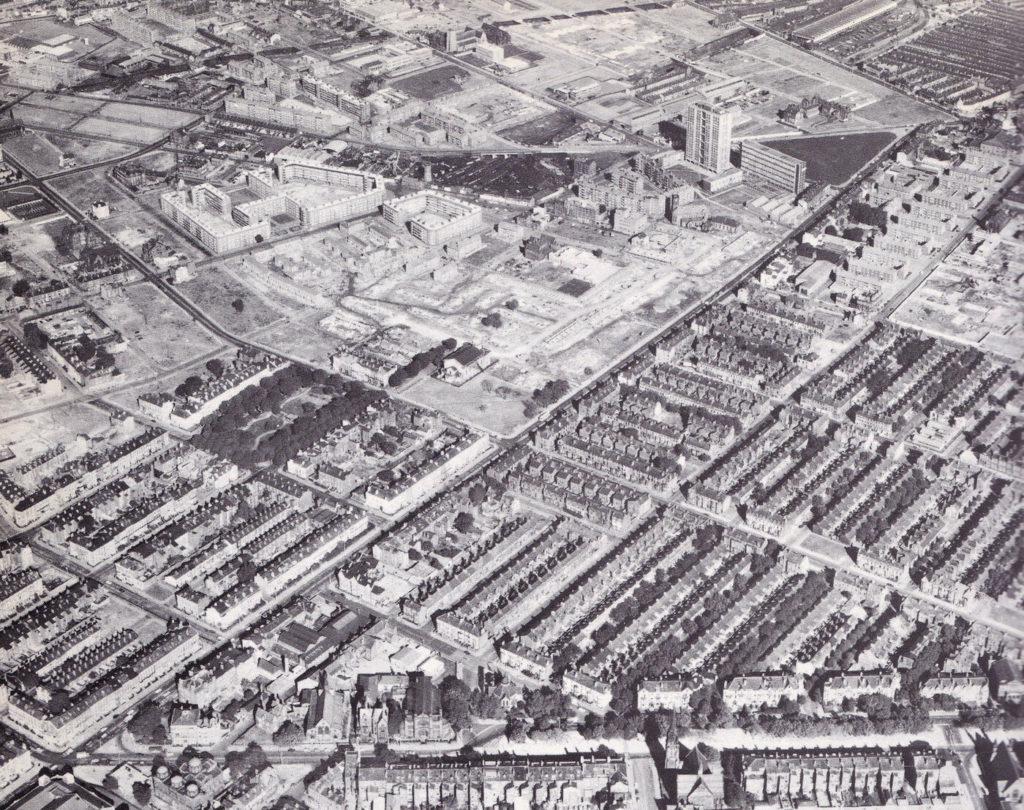

Larissa Fassler builds and draws space. Yet nothing here is cleaned up or ordered according to scale. In the large-format drawings of cities, she shows us what we experience when we walk over traffic islands, through underpasses, and passages, or into the entrances of buildings. The artist overlays the built space with appropriations. She observes and walks through the space over and over again, collecting and mapping what she finds. This is also the case with her work Kotti (revisited). The many fragments layered on top of each other tell stories of a complex space that proudly says: »I am city. I am neither easy to understand nor easy to plan. I will defend myself if you seek to question my existence.« The big colorful picture calls for planning to take care of and work with lived space instead of against it. Because where is this city going to go if it has to leave here?